The Power of Street Art

Social Studies - Grade 7

This unit of inquiry is not a recipe book but rather a launchpad to inspire new BIG IDEAS. We encourage you to use and/or modify one, or several of the BIG IDEAS below. Adapt it to the grade/ ability level of your students.

Enduring Understanding

Street art fosters and explores the relationships between art, audience, location, and politics.

Guiding Questions

How does street art provoke controversy, transform the landscape and inspire social change?

How can street art disrupt accepted hierarchies in art and culture?

How can street art serve social justice?

Mind Opening

Choose or devise practices to encourage students to be open to new experiences and ways of thinking in your classroom. For example, the MindUP in-school program.

Discovery & Inspiration:

Launch the Project

• Introduce the Theme: Present the Enduring Understanding and Guiding Questions using vocabulary that is appropriate for your grade level.

• About Vancouver Biennale: Play a short video.

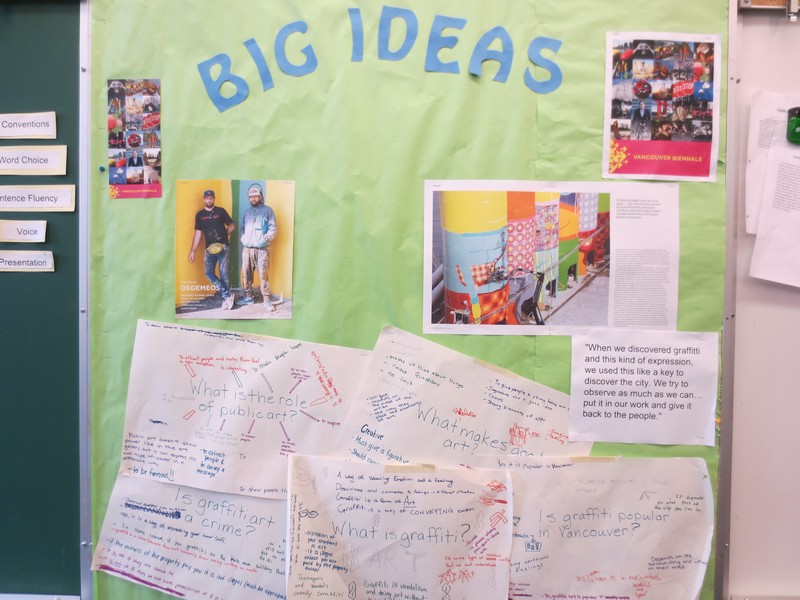

• Create Project Space: Brainstorm ideas to make the project theme visual and visible using bulletin boards, and/or a project corner to share relevant materials and inquiry questions and processes.

Reference Resources:

• Introduction to Sculpture and Public Art Unit Plan for information on how art has evolved over time and the unique experience sculptures and/or public art brings.

• Vancouver Biennale 2014-2016 Exhibition Theme: Open Borders / Crossroads Vancouver

• About Artist and Artwork (PDF)

Other Resources

Covered in the Reference Material for Inquiry Challenges list of this unit plan

Learning to Learn:

Art Inquiry

• Make a visit to Granville Island Ocean Concrete to view Giants (OSGEMEOS, Brazil) on the cement silos and encourage students to freely explore and interact with the art pieces individually and in groups OR

BIG IDEAS Anywhere educators: View the Giants Guided Tour Video MUTE ON and encourage students to explore at different angles individually and in groups.

• This Art Inquiry process enables the students to practice observing, describing, interpreting, and sharing visual information and personal experiences.

• Use the Art Inquiry Worksheet (PDF) to guide and capture their ideas and impressions. Customize or create your own Art Inquiry Worksheet as appropriate for your project and class needs.

Shared Insights

• Sharing Art Inquiry Experience: Ask students to share the Art Inquiry Worksheet responses in class.

• View Guided Tour Video: View the Giants Guided Tour Video again with SOUND ON.

• Significant Aspects of the Artist’s Life & Work: Using the following About Artist and Artwork (PDF), OSGEMEOS website and this Georgia Straight Article. Teacher creates stations detailing Gustavo and Otavio Pandolf’s (OSGEMEOS) life and work. In small groups, students rotate through these stations. Topics might include: (1) education and training; (2) life’s work; (3) materials and processes; (4) beliefs and values. At each station, students answer questions and/or complete tasks. For example, at the station “life’s work” students might plot the artist’s various installations on a map of the world. Encourage students to draw a parallels to their own lives and reflect on the countries/cities/communities that they have lived in and the significance of these location to them.

• Artist Themes: Transformation– How does OSGEMEOS’ work reflect transformation in society? Show students images of OSGEMEOS’ work in locations throughout the world. Students brainstorm possible preliminary answers to this question. Teacher records these and posts them in a visible area of the classroom. Introduce the three guiding questions: How does street art provoke controversy, transform the landscape and inspire social change? How can street art disrupt accepted hierarchies in art and culture? How can street art serve social justice? Reinforce that the purpose of this inquiry is to delve further into these questions and that answers and understandings are meant to evolve and change.

Inquiry Challenges

• Introduction Graffiti Art and Street Art – How is street art both provocative and controversial?

1/ Show the following Short Clip from the documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop.

2/ Consider introducing street art with a multimedia display of different artists’ work (see options below). Individually, students to investigate and complete Part I of their Introduction to Street Art Worksheet (Word) and share their answers in pairs.

3/ Set up 6 stations displaying one piece of artwork from 6 different graffiti/street artists from around the world (see potential artists below).

4/ Students to brainstorm and connect through a Graffiti Teaching Strategy (PDF) rotating in groups thorough the stations, viewing the art and responding to it graffiti style.

5/ Students rotate through the stations a 2nd time to view all responses.

6/ Post classroom generated graffiti responses for discussion.

7/ Consider using this quote by Otavio “You don’t see many murals or graffiti in the city [of Vancouver]. They really control and really go against it. That’s sad. That’s really sad,”. Students engage in a Four Corners Activity in reaction to this statement.

Helpful Web Sites: Banksy (UK Artist); Corey Bullpitt (Canadian Haida Artist); Panmela Castro (Brazil); The 50 Most Influential Street Artists of All Time; 25 Street Artists From Around The World Who Are Shaking Up Public Art

• Street Artists & Current Social Issues – How do artists use the streets to comment on current environmental and social justice issues in society? What are other street artists making statements about?

1/ Teacher-led discussion: Where is Brazil? What important event took place there in 2014? What is domestic violence?

2/ Brazilian street artists used the spotlight of the World Cup to highlight a problem close to home – domestic abuse. Consider using this PBS News Hour video that introduces this story from July 15, 2014.

3/ Discuss the video and show some images of Banksy’s Work that reflects his social commentary.

4/ Students might work in small groups prepare and present a multimedia presentation using PowerPoint or Prezi to the class that introduces current environmental and social justice issues that other street artists are addressing though their work. Presentations might touch upon the following topics: Career; Notable Artwork; Technique; Political & Social Themes; Personal Identity and Critics.

Helpful Web Sites: The 50 Most Influential Street Artists of All Time; 25 Street Artists From Around The World Who Are Shaking Up Public Art

• Historical Perspective & Historical Artwork: The Influence of Time and Place – How does art reflect the culture and world in which it was created? What does other artwork art tell us about the time and place of its creation, and what does this context tell us about a work of art? Art has always been a reflection of the world in which it was created. Street art reflects our ever-changing world and its impermanence ensures that it might not last long enough for future generations to admire, examine and honour.

1/ In pairs, students choose an artist covered by the concepts and content of Social Studies 7 Curriculum (World History & Geography 7th to 15th Century). Suggested Sources: Online Museums & Art Galleries (PDF) or another site like Google Art Project students

2/ Teacher reviews the concept of Historical Perspective with the following video.

3/ Students research the historical, social, cultural, intellectual, and emotional setting of the artist’s lifetime using Online Museums & Art Galleries (PDF) or a site like Google Art Project.

4/ Pairs read reviews written by art critics to learn how the art was originally received and how it is viewed today. Students trace the legacy of their chosen artist via the work of artists who came later or their effect on culture.

5/ Partners create slide shows using a video-creation platform like Animoto that gives users the power to create and share beautifully animated videos that showcase the works they selected. Students can caption them, add relevant contextual elements (historical events, cultural trends and fashions, for example) and put them to music. Educators can get a free account at http://animoto.com/pro/education

6/ If research reveals that a particular piece is a reaction to something in the artist’s experience or events in the world, ask the students to explain that, and identify any influences — other visual artists, musicians, filmmakers and so on.

7/ Questions for consideration: When was this work produced? What might have been the artist’s purpose in producing this art? Who do you think is the intended audience? What do you think is the intended message? What was going on in the society where this artwork was created that might help us interpret the artwork? How might this context help use understand what life was like for the people in the artwork? What materials has the artist used? Is there special significance to these materials? What symbols or metaphors does the artist use? What might this artwork suggest about its creator? What might have been the artist’s purpose in producing this art? How does art reflect the culture and world in which it was created?

• Continuity & Change: Street Art & Granville Island– How has Granville Island changed over time?

1/ Begin with the following Short Video that discusses the transformation of Granville Island.

2/ Teacher introduces/reinforces the concept of Continuity & Change.

3/ Using the Vancouver Archives Search Results for Granville Island and other Web sites, students to select three images of the area from different historical time periods and document dates and citations and saving them.

4/ Students select three more recent images (one of which should be as close as possible to the current year) and do the same.

5/ Groups collate photographs and text by using a digital timeline generator like Capzles* or by producing timelines on larges sheets of paper.

6/ Teacher can lend support through the History of Granville Island Web site.

7/ Groups answer to the following questions as a class: What does the story of your timeline show? What has changed the most on Granville Island? What has changed the least? Are there turning points in the change that has occurred? Were there times of more continuity or more change? How could your timeline be divided into chunks or periods? What events might be most important for tourists? What events might be most important for business owners? What events might be most important for environmental advocates?

8/ After viewing all the timeline presentations the teacher can challenge the students to answer the question: Do you think the changes on Granville Island reflect improvement or decline? Why? Students are asked to take into account economic change, social and cultural change, and environmental change.

9/ Visit Granville Island Ocean Concrete to view Giants (OSGEMEOS, Brazil) on the cement silos and encourage students to freely explore and interact with the artwork when students visit the artwork. Consider having them take their own digital images using their smart phones and add them to these timelines OR BIG IDEAS Anywhere educators: View the Giants Guided Tour Video MUTE ON and encourage students to explore at different angles individually and in groups.

10/ Culminating question: How Os Geomos’s Giants transformed the landscape on Granville Island?

*(Capzles is a free iTunes app accessible from any computer. It allows users to tell a story using pictures, video clips, audio tracks and text. Users can place this media, called “moments”, together chronologically in a timeline. The result is called a “capzle”. Moments can be viewed individually, or all can be viewed in progression. Capzles can be shared with friends by sending an email link.)

Student Creation & Taking Actions

• Reacting with Graffiti to Historical Art – How can we use historical art to comment on current environmental and social justice issues today?

1/ Class might read and discuss the NY times article “Need Talent to Exhibit in Museums? Not This Prankster” and shares images of Banksy’s work: Wooster Collective or 25 most expensive Banksy works.

2/ In pairs, students re-read the article and answer the Banksy Article Questions (Word)

3/ Teacher distributes colour photocopies or printouts of an historically significant painting covered by the concepts and content of Social Studies 7 curriculum (World History & Geography 7th to 15th Century).

4/ Students work in pairs to meaningfully “graffiti” this famous painting.

5/ Students first research their historical works of art.

6/ After completing research and analysis, pairs might alter their assigned painting and prepare an artist’s statement explaining the “graffiti” they added (Whenever possible, students should use historical information about their painting to explain the changes they made.)

7/ Final products could be displayed in the classroom or in the school’s hallways as an exhibit.

Digital Technology/ Geography: Regions & Locations — Mapping Granville Island using Thinglink

Before going to Granville Island, print out a map of the Island. Distribute to students. Also create a digital jpeg of the image to upload to Thinglink. Students are assigned different regions & locations of the Island to document. As students visit their region, have them take pictures and make videos. These become touchpoints on the digital jpeg of the image. Thinglink allows multiple users to edit, so if there are several young people who went on the trip, they can each bring to life their area of the museum. You can see an example of what this looks like here.

Reflection

• Teacher and students can reflect on their entire learning process by revisiting the Guiding Questions:

How does street art provoke controversy, transform the landscape and inspire social change?

How can street art disrupt accepted hierarchies in art and culture?

How can street art serve social justice?

• How did the unit of study open inquiry, create cross–curricular learning opportunities and/or apply learning to real life situations? Has this unit of inquiry changed your opinions, values and worldview? In what ways, if any, has it helped you grow as a learner?

Ideas for Cross-Curricular Access

• Language Arts: Expressing a Persuasive Argument About Street Art –

Can writing change a person’s opinions and/or worldview? Perhaps one of the best and most widely recognized examples of persuasive writing in action is the classic editorial.

1/ Inquiry into what students know: What is an editorial? Have you ever read one? What is the purpose of an editorial?

2/ Teacher may show NY Times editorial page editor Andrew Rosenthal’s Brief Video and give students his 7 Pointers Summary (Word).

3/ Teacher selects an editorial on street art to read, copy and distribute. Samples: LA Times; NYPost; CanWestGlobal.

4/ Teacher might read the editorial aloud and students complete Part 1 of the Persuasive Writing/ Editorial- Format Worksheet (PDF) in pairs.

5/ Students use Part II of the Persuasive Writing/ Editorial- Format Worksheet (PDF) as a guide to draft their own editorials on Street Art.

6/ Drafts are peer edited to revise ideas, organization, voice, word choice and sentence fluency.

7/ Editorials may be read aloud and/ or posted to classroom blog.

8/ Students may comment on the editorials or responses to these editorials on the blog.

• Fine Arts:

1/ Stencils with Social Impact – This amazing Stealthy Stencils art project that has students cutting an images into the bottom of paper bags to brown bag to covertly graffiti the sidewalks! Make sure their stencil has meaning and speaks to a social issue of importance to the students.

2/ Creative Painting – Encourage students to use anything but paintbrushes to create artwork. Try sticks, washable kitchen utensils, plastic utensils, etc., as OSGEMEOS experimented with materials in their early years! Fill spray bottles with diluted paint–tempera or diluted acrylic may work –to give students the chance to ‘spray’ paint. Older students could use real spray cans outdoors.

Credits

Written by: Stephanie Anderson Redmond, B.A.; B.Ed.; M.Ed.; Ph.D. Student, Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy, UBC

©2014 Vancouver Biennale

Related Material

Kerrisdale Elementary: Public Art, Power & Populace

Kerrisdale Elementary: Public Art, Power & Populace